Photos below by D.Kakkak

A Summit Overview

Building on the success of the 1st Intertribal Food Summit in Oneida, Wisconsin with a handful of producers in 2012, the Great Lakes Summit has since grown into a successful forum for discussing a wide range of issues facing the food sovereignty movement in the western hemisphere.

The event has since been held at the Jijak Center owned by the Gun Lake (Match-E-Be-Nash-She-Wish) Band of Potawatomi in southern Michigan, the Red Lake Ojibwe Nation of northern Minnesota and the Sac and Fox Meskwaki Indian Community at Tama, Iowa. In 2019 the event was held at the Rodgers Lake Campus on the Pokagon Reservation near Dowagiac, Michigan.

The 2019 event hosted by the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance and Intertribal Agriculture Council (IAC), welcomed over 700 participants from Indigenous communities through-out the world to the five day event. A concurrent Youth Summit component was run alongside the entire event.

One of the ideas behind the food summit was to understand and know the plants, medicine and properties of the natural world, and therefore the abundance of food and eatable forest products that are found within a community’s living radius.

That means in one sense, heading back out into the local woods and that is one of the first activities among the more than 55 sessions offered this year at the food summit, including several walking classes, such as those pictured below.

The food summits are not organized like regular conventions that Indian Country and many participants typically participate in. While there were a couple dozen workshops and presentations during the more than 55 sessions offered using computer screens and modern digital presentation capabilities, like Power Points and video, the vast majority of the workshops were developed with hands on activities in mind, to get attendees involved producing a tool or piece of equipment, or experiencing a food product production.

The 55 workshops offered, featured over 70 speakers and presenters and almost always a around table of questions and answers from those growing, harvesting and foraging food in the field.

The summit with the support and endorsement of the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi was opened with a welcome from Tribal Chairman Matt Wesaw (below in blue), and a veterans color guard and prayer ceremony from local elders. The entire event was conducted with strategic local support from several departments within the Pokagon Tribal Government. The main community committee involved in planning over the course of the year leading up to the summit was the Pokagon Food Sovereignty Committee with tribal council member Gary Morseau providing key liaison support.

Departments involved in planning and implementation included the

Health Department, Law Enforcement, Public Works and Maintenance who

helped set up the event site, took care of both the Rodgers Lake Campus

site where vendors, hand on demonstrators and speaking facilities were

located, in addition to maintaining the tribal camp and lodging

facilities for housing of participants.

Another key department

player was the Four Winds Casino, where coordination of unique food

orders from Indigenous chefs coming in from around the world took place.

Coordinating income food sources is difficult but necessary to the

success of each and every unique culinary approach taken by chefs from

different regions and tribes.

Chefs, traveling from North and

South American alike bring interesting food presentations from their

region, but getting those food products sourced properly, shipped and

stored presents a unique challenge. Just where do you get a cooler full

of northern Wisconsin walleye fish eggs and how can it be transported

and then stored? Cactus from the southwest, cocoa from South America,

special spices, elk meat and other locally sourced food needs can get

complicated, but one of the purposes of the food summit is to help

increase the inventory of product availability, find recipes for their

culinary use, and then finding a willing clientele to eat or buy it.

Coordinating those supplies is crucial to the culinary tastes and needs of the chefs and participants, taste testing.

The workshops and presentation sessions offered everything from making Iroquois planting sticks, learning about a no-till organic approach to farming, elm bark harvesting for containers, or lodging structures, introduction to seed saving, seed exchange, traditional tools, identification of local foods and eatable flowers, community foods systems and preparations sites, ceremonial feasting cycles and creating business plans were a few of the offerings. The summit worked to provide a combination of both traditional and the modern presentation opportunities.

“How do we feed our communities again? That’s what it’s really all about and getting to that point where we can be bringing the foods back into our diet” as Great Lakes Intertribal Agriculture Council coordinator Dan Cornelius explains it.

The Native American Food Sovereignty Alliance which started a culinary mentor program generated applications from over 60 Native chefs and cooks this year. Each year the number of chefs and mentors who want to be part of the program has increased. Additional volunteers helped with all kinds of activities from gathering special ingredients in the woods, to helping serve meals as a way of breaking into the industry.

Some well know names in the Indigenous culinary sector included names like Sean Sherman, the Sioux Chef, Arlie Doxtator from Oneida, Wisconsin, Ben Jacobs of Tacobe in Denver, Colorado, Vernon Defoe of Red Cliff,…. a fantastic lineup of established chefs. Those well known chefs were paired with mentors from through-out Indian Country. Over 60 chefs and mentors fed a registered crowd of 700 people from inside a pavilion kitchen, and mobile food truck and outside woodland cooking facilities.

Over 600 pounds of corn, 30 gallons of maple syrup, whitefish and lake trout from Lake Superior, walleye from Red Lake, Minnesota, walleye eggs from northern Wisconsin, a whole buffalo from a nearby farm, trapped beaver, venison hind quarters, ducks, blue potatoes, sunchokes, pounds of wild rice, hickory nuts, tepary beans, cactus, white corn from Iroquois country and a couple of muskies for underground cooking were only a partial list of ingredients brought in for the summit.

The summit partnered with Pokagon Health Department and on a voluntary basis had some participants draw blood for checking sugar levels and other data at the beginning of the event. Then a second blood draw at the end of the event to quantify the impact of eating a Indigenous diet for several days, especially with foods with a low glycemic index and what kind of an impact that would have on participants.

The construction of tools in a traditional way is meant to help to strengthen the connection and personal relationship to the foods, whether seeds, foraging, raising animals or butchering techniques. Doing everything from working with the earth and soil, preparation and incubation of seeds prior to planting, planting songs, ceremony, and use of traditional equipment for farming represent a healthy cycle for growing food, hunting and foraging in a holistic way.

While embracing the traditional thinking approach to harvest,

foraging and use of foods, the summit also featured up to date modern

approaches to real needs, laws and farming techniques. The United States

Department of Agriculture, (USDA) provided classroom workshops and

guidance on numerous activities to help potential farmers, harvesters

and prepare those to manage their way through numbers, business

outlines, federal, tribal and state laws on food and food handling.

Participants to the summit engage USDA and other regulators on site on

issues of traditional and ceremonial handling of foods in order to

mitigate rules and regulations that might impact Indigenous culinary

customs.

The Pokagon Band had both a food and health inspector on

site checking for food safety issues. Working side by side with chefs,

food inspectors and health officials were also able to pick up pointers

on how their own local tribal ordinances could reflect conflict

avoidance issues, while safe guarding the public from mishandled food

processing techniques.

Previous efforts have led to US commodity food programs, tribal education systems and elderly feeding programs moving toward providing a more traditional and healthy diet being served locally. A good example is finding wild rice and onions, venison, and local fish being placed on federal feeding menus or being available through the USDA commodity foods programs for people to choose from.

On the other end of the spectrum, Arlo and Lisa Ironcloud from Pine

Ridge, South Dakota led a workshop with at least 30 others people

helping to butcher a buffalo. Their presentation includes highlighting

different cuts of meat and helping others to have a better understanding

of the sacrifice that the animal made to feed people. The Ironclouds’

butcher in the most respectful way they can, while meeting food code

regulations for storage, cleaning, use of tools, cooling and handling of

meat.

The buffalo butchered helped feed 700 people in a couple

of different meals with offerings of buffalo ribs, buffalo stew

thickened with parched white corn, and bison tamales at one meal alone.

By the end of the conference, some participants had eaten bison in a

dozen or more recipes and different preparation techniques.

Participants were also able to work hands on with many presenters and included the opportunity to forge their own copper tools, hollowing out a yellow birch wooden corn/grain grinding mortar, carving out a planting stick or cooking paddles, gathering and making birch bark or black elm baskets, and forming birch cones for holding hardened maple sugar. Other classes made corn husk dolls, winnowing baskets, and several participants had the fun of tanning several different types of hides.

Even the outside kettles over the fire are examples of food sovereignty knowledge, the knowledge of how the fire changes the flavors of food, the textures and uses of several food products. A good example is the making of white corn into hominy increasing the nutritional value of the corn by making certain elements more digestible in the human stomach.

Here we show some of the value of a hands on workshop. Many participants went home with tools and products they helped forge, cut, mold, tan or build. In most cases this experience started in the woods with a simple ceremony of thanks, the harvesting of a product, and then the steps needed to turn a piece of nature into some kind of functional tool or food for human beings.

Through-out the summit, many participants engage in cross discussion on relevant topics from planting and garden bed preparation, hunting and cooking techniques, flavors and historic trade routes. Out of discussions about historic trade routes came discussions about trade and barter, exchange, timing of harvesting and use of new products in a world of invasive species and climate change. One workshop related to reed mats was conducted but using a local invasive reed species as a way of attempting to limit, or eradicated one kind of invasive species in the Great Lakes or maybe turn it into a local economic endeavor of some kind. One mantra of the summit was to simply, “think out of the box.”

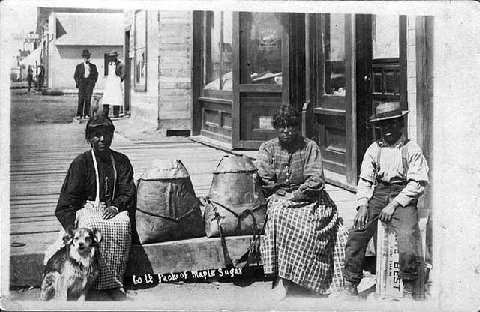

One of the sweetest topics of the summit gathering each year is the maple and sapping section. Here, several tribal efforts has increased production of maple sugar, a historic product that once generated what would be the equivalent of millions of dollars in modern day economic value. Wisconsin and Michigan tribes in 1865 sold close to 450,000 pounds of maple sugar.

But while digging for information on maple sugar, participants also

used historic techniques to make sure — boiling a batch in clay pots on

coals, a much more likely historic likelihood from the narrative that

Indians dropped red hot stones into clay or birch containers to thicken

their sap and boil it down to sugar.

But discussions and

entrepreneurship have added many new products. This year at the summit

you could find (and in some cases procure) traditional maple candy

containers made of yellow and white birch to cases of maple vinegar

being offered for sale by various tribal vendors. Products of maple

sugar, and syrups of many sizes were available but the overall efforts

were to get participants to the comfortable point of being able to go

out into their own yard and tap one or two trees for drinking tea or

cooking with. The workshops worked from one tap — all the way up to

modern techniques for tubing and the ethics of reverse osmosis (RO) in

de-watering your maple syrup. Any topic or question in-between was game.

A major and wonderfully colorful topic of each year, almost emotional

in some of its impact has been seeds and seed exchanges. The whole

bases of the food sovereignty movement might not be possible if it were

not for the unique and almost spiritual existence of a huge diversity of

Indigenous seeds. Over 600 varieties of traditional Indian corn alone,

and counting for one type of plant. Remote and unknown varieties of

tribal corn are still unearthed in museums and private collections. Hopi

Blue Corn for tortillas are well known, but the Hopi have several other

corn seed as well, some used because it has low sugar for elders, other

types used for ceremonial needs like weddings and funerals.

What-ever

is going on with seeds, is surrounding by the feeling of a blessing of

some kind. Seeds….. Indigenous seeds showing up to feed us with corn,

beans, squash, sunflowers, watermelons, and hundreds of traditional

plants once again thriving to feed our communities. The summit brings

together some of the best know seed rematriation people in Indian

Country.

Rowen White and the Indigenous Seed Keepers Network have been

rematriating seeds for a number of years and you can find the fruits of

those seed exchanges growing in gardens across the North American

continent today. These efforts are on-going from local seed exchange

events to a recent field museum in Chicago rematriating seeds they found

in their collections back to Meskwaki Nation at Tama, Iowa. Many of

these seeds are historic seeds once commonly used in our community

hundreds of years ago, and some varieties described in history books had

been thought to have been lost for ever.

The Intertribal Food

Summit brings all of these elements together, from history to culture,

from the very earth and soil, to modern regulations to keep our food

safe.

The summit exists in part to serve our communities throughout North America with a healthier diet, stronger economy and one of the most delicious palates the Indigenous community can serve up.

For more information regarding future Great Lake Summit gatherings, proposals for future or related events contact Dan Cornelius at dan@indianaglink.com

Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe elder George Martin, assisted by Buddy Raphael (not shown) discuss the boiling process for making parched corn into hominy. Raphael says he likes to let his corn dry for over a year before using it for cooking and other needs.

Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe elder George Martin, assisted by Buddy Raphael (not shown) discuss the boiling process for making parched corn into hominy. Raphael says he likes to let his corn dry for over a year before using it for cooking and other needs.